The Rare Seth Klarman Interview No One Talks About – Until Now

Seth Klarman’s rare 1991 interview provides a masterclass in value investing, capital preservation, and contrarian thinking.

TL; DR

Seth started investing at age 10 and later worked at Mutual Shares under legendary investors Max Heine and Michael Price. He co-founded Baupost Group in 1982 with US$27 million AUM, growing it to US$400 million by 1991, primarily through compounding and turning away institutional investors.

He buys undervalued, asset-rich businesses and securities with predictable cash flows, focusing on a margin of safety. He avoids speculative, growth-based projections and prefers tangible assets over uncertain future earnings.

Klarman finds investment ideas through reading financial media, tracking spin-offs, distressed securities, and exploiting institutional inefficiencies (e.g., forced selling due to credit downgrades). He looks where others aren’t paying attention.

He criticizes institutional investors as short-term, performance-driven "fully invested bears" who follow market momentum. He warns that a market downturn could trigger a rush to exit, amplifying declines.

Seth argues indexing drove markets higher but could exacerbate a decline if institutions withdrew capital simultaneously, leading to significant losses.

Q: What attracted you to the investment business?

Klarman: I've always been interested in the market. I noticed a column of numbers in the papers, and I was always mathematically inclined. So I was interested. I traded my first stock when I was 10.

That’s how this 1991 Barron’s interview with Seth Klarman begins. Seth traded his first stock, Johnson & Johnson, when he was just 10 years old. His first experience proved fortuitous when the stock split 3-for-1 the day after he bought it.

His real education in investing came during a summer internship at Mutual Shares, working under legendary investors Max Heine and Michael Price:

They invited me back to join them in January of '79. I worked there about 20 months until I left for business school. Just before graduation, I was offered the opportunity to join with several individuals who had decided to pool their assets and helped to form the Baupost Group to steward those assets.

Baupost Group was formed in 1982 with US$27 million AUM and at the time of the interview, it already managed US$400 million. No institutional money: only the individual money of the partners:

We set out at the beginning to be somewhat unconventional, with our clients acting as board members and as part owners. The incentive really was to do whatever it took to maximize the return on their money, not necessarily to grow a profitable business. Along the way, some decisions were made, including one to turn down most of the people who tried to become clients. We actually closed for new clients about five years ago. And we have grown from compounding ever since.

Over the years we have grown through word of mouth. In the earlier years, we grew beyond the initial three families, for a couple of reasons. One was that they had some friends who liked the idea of what we were trying to do and wanted to come in. They are the kind of people who say yes to friends. And also partly because we didn't want to be overly dependent on any one person for the success of our business going forward.

Seth reveals that they were not a hedge fund per se because they did not hedge and rarely shorted, but they were compensated like a hedge fund:

We tend to be long investors. We are rarely on the short side.

During the interview, Seth discussed how The Baupost Group performed during the 1987 market crash:

Q: How have you done during stressful periods? Let's say 1987?

A: I would argue a little bit about the definition of stressful periods. Because I will tell you I get more stressed when the market is running up than when it is running down.

We have historically done very well in down markets. Our general predisposition is that we ought to run our money as if it is our own.

We tend to only make investments when we think there is a compelling opportunity being presented. And often we will hold a third or half in cash or even more, awaiting such opportunities. As a result, while we do not do any allocation based on our view of the macro economy or top-down view of the market, by looking bottom-up for opportunities and failing to find them, that tends to self-regulate.

In that year, Baupost was holding a significant amount of cash—between 40% and 50%. This high cash position put them in a favorable position, as they were not heavily exposed to market-sensitive securities. For example, one of their largest positions was in the senior bonds of Texaco, which was in bankruptcy. Although these bonds did decline in price during the crash, they did not drop as severely as the broader market, and they quickly bounced back.

He then comments that being a small firm has its advantages, especially when they have an "eclectic strategy":

There are dis-economies of scale in terms of the returns that can be earned on managed money. That probably kicks in a lot smaller than we are. It probably kicks in at $50 million or $100 million. But over the realm of all possible sizes, you just don't want to get beyond a certain level, particularly when you have an eclectic strategy like ours. There is only so much that you can buy that fits our kind of criteria. And we are comfortable at our current size.

I think we also want to stay small because it is frankly more fun. We enjoy the camaraderie of being a small firm with everybody doing work, and everybody understanding pretty much where we are going. The last thing I want to be is manager of a staff of a dozen analysts and portfolio managers. I wouldn't like that at all.

Value investing philosophy

Seth is a classic value investor: He likes buying a dollar’s worth of assets for 50 cents. However, is not rigid in this definition. He seeks to buy dollars for 40 cents or even 60 cents if they are attractive enough. According to Klarman, value investing is about being realistic and conservative when evaluating investments.

He avoids making optimistic forecasts about future cash flows or assuming growth. Instead, he focuses on what is already there, looking for businesses with tangible assets, strong balance sheets, and predictable operations.

We certainly don't stick to it rigidly. We will buy dollars for 40 cents, or dollars for 60 cents when they are attractive dollars to buy. I think that we implement it a fair bit differently than many value investors or many so-called value investors who frankly I'm not sure are buying good value at all. Value to some extent is in the eye of the beholder. It is very hard to pin down what the value of a future set of cash flows from a business, be it cable TV or biotechnology, is going to be. Some are easier to predict than others. But it is very hard to predict what those future cash flows are going to be. And it is very hard to ascertain the correct discount rate to bring them back to the present with.

Being a conservative investor, he doesn’t pay attention to the future or growth; he prefers to focus on the "now":

When we look at value, we tend to look at it on a very conservative basis -- not making optimistic forecasts many years into the future, not assuming growth, not assuming favorable cost savings, not assuming anything like that. Rather looking at what is there right now, looking backwards and saying, Is that the kind of thing the company has been able to do repeatedly? Or is this a uniquely good year, and is it unlikely to be repeated?

He prefers to focus on asset-rich companies with predictibable business:

We tend to look at hard assets as much as possible. For instance, cash is something we understand. When a company has cash on the books, or marketable securities on the books, we think we understand that. And the more you get into businesses that depend on things going right in the future, the harder we find it to understand it. So we tend to buy asset-rich businesses, very predictable businesses. But perhaps most important, we are not just focusing on equities. We focus on any security of a company that is mispriced. We can even find some companies where one security, like the equity, is overvalued, but where another security, like the debt, might be undervalued.

Idea generation

The Oracle of Boston revealed that approximately half of their investment ideas originate internally through a systematic and disciplined research process. This involves:

1. Reading newspapers and periodicals, like Barron's

2. He look for opportunities caused by market inefficiencies or imperfections. He noted that these inefficiencies are often created by institutional constraints and forced selling:

One thing we want to look for is perhaps a market inefficiency or imperfection. And often these are caused by what we would call institutional constraints. The institutions, first of all, because of their tremendous size, and second of all, because many have gotten away from fundamental investing, tend to be prolific creators of opportuni ties. An example of this would be when a large company spins off a much smaller subsidiary and distributes the stock free to shareholders. The institutions tend to be natural sellers of the spinoffs.

3. Special situations (spin-offs and distressed securities):

When in the newspaper it mentions that such company is considering a spinoff, we will follow the progress of that and look at the registration statement when it becomes available for a posible investment. There are, of course, now people who follow spinoffs, including an analyst at one major firm. So even in that area there might be fewer opportunities than before. Although every so often one slips through the cracks, or one is written up but ignored by most of Wall Street. We do find some opportunities even in overpopulated areas.

Another type of rock we would look under would be when securities get downgraded from investment grade to below investment grade, i.e., distressed. In particular, many funds that own these are not permitted to own other than investment-grade securities. So when the downgrade happens, they have to sell, they have no choice, given the rules that they operate under. That may create a short-term supply/demand imbalance. Another opportunity created by selling that is not dictated by fundamentals.

4. Conversations with partners and clients: Although Baupost’s clients occasionally suggest investment ideas based on their own business knowledge, Klarman noted that none of these suggestions have translated into actual investments:

I would describe it this way: When you have been doing this for a while, you start to become more proficient about where to look, which rocks to look under. The rocks we look under tend to have a few things in common.

The problem with institutional investors

According to Klarman, institutional investors often focus on short-term performance and relative benchmarks:

The institutional investors, being short-term and relative-performance oriented, are trying to all beat each other every three months, and hence will react to which ever direction the market is going in. As long as the market is generally flat to rising, they will stay in the market. But if they perceive that the market is going down -- in other words, if the market starts to go down -- they may all decide to get out at once, none of them wanting to be in longer than anybody else. We have put on a few circuit breakers, but they don't address the fundamental problem of professional investors who feel compelled to stay in and hold overvalued securities.

The problem with indexing

He also discussed the risks associated with the increasing trend toward indexing. He argued that indexing had been a powerful stimulant for the market on the way up, but it could have the opposite effect if the market began to decline:

There is no question that indexing exacerbated the market movement upward. If we have a bad year or two it is easy to envision that institutions that had money in indexing might pull it out en masse, exacerbating the decline. The other thing I want to make clear is that when we think the market is overvalued we don't believe it is 5% or 10% or 15% overvalued. What concerns us is when we look at most securities, we wouldn't buy them if they dropped by a quar ter or a third. We think these are substantially overvalued securi ties, or at least are valued a quarter or a third above where they become interesting buys. When people say I want the market to go down so it will create opportunities for me, it sounds like the purpose of market declines is simply to create opportunities for people with cash. We don't believe that. The ironic thing is that the market could decline in our view 750 or even 1,000 points, and might still not be at bargain levels.

The problem with buying the dip

Seth observed that many investors had become conditioned to see every market decline as a buying opportunity. This attitude was shaped by the market’s behavior during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when declines in 1987, 1989, and 1990 were all followed by new highs. He believed that this behavior was dangerous because it created a false sense of security and could take time to correct:

I think investors always learn the lessons of the recent past. And that is the lesson. The lesson is that any crash, any decline for any reason, whether it is a war or whether it is a 500-point one-day drop, or whether it is the blowup of a major take over, whatever it might be, is, in fact, a buying opportunity. People are conditioned to buy on any decline, on any bad news. We think that that is the kind of thing that it might take a while for people to be weaned away from by the punishment of having the market not rebound. But to us that helps to explain why, when things are as bad in the economy as we perceive it, the market hangs in there. This may take longer to correct.

His three favorite investments

Columbia Gas System

It was one of Klarman’s favorite investments in the distressed debt space. The company filed for bankruptcy in July 1991 due to issues with gas-purchase contracts that were significantly above market prices. Klarman compared the situation to the successful Texaco bankruptcy workout, where Texaco’s senior bonds recovered and generated significant returns for investors.

Columbia’s liabilities were largely known and appeared manageable. Despite the bankruptcy, the company’s assets seemed sufficient to cover all liabilities, including the gas-contract liability.

He believed that these bonds would eventually be repaid at par plus accrued interest, making them a relatively low-risk opportunity. The bonds were trading in the high 70s to 90s at the time, offering a potential yield of 18% annually if the company emerged from bankruptcy as expected.

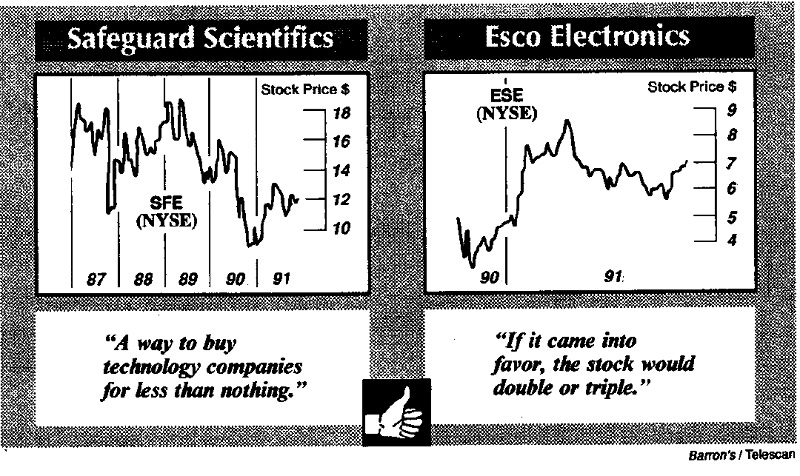

Esco Electronics

This one was a "classic Graham & Dodd situation": Esco was a spinoff from Emerson Electric and traded at a fraction of its tangible book value. Klarman valued Esco based on its assets and cash flow, rather than its earnings.

Trading a tangible book value of $17-$18 per share vs a stock price of $6 1/2 per share, the company had virtually no debt, and its cash on hand was almost equal to its market cap. It was cash flow positive via D&A and was reinvesting that cash flow into the business.

Esco had entered into several fixed-cost development contracts that tied up working capital and created short-term losses. Klarman believed that as Esco freed up working capital from these contracts, it would generate several dollars per share in additional cash over the next few years.

There has also been insider buying, which is one of the things we look for. The chairman seems like an excellent manager and we appreciate the job he is doing. We think he is doing all the right things, looking at cash flow, and not worrying about earnings comparisons at this point. And certainly not trying to grow the business. He is trying to do the right things for shareholders. He put some money into the stock both at $3 or $4 and then again at $6 or $7. So, he has put his money where his mouth is. Although we would like him to buy some more.

Safeguard Scientifics

The company was a diversified holding company involved in technology and venture capital investments. Klarman’s initial interest in Safeguard Scientifics was driven by its large stake in Novell, a leading company in local area network technology.

At the time Baupost first invested, the value of Safeguard’s stake in Novell was equal to Safeguard’s market capitalization, meaning that the rest of Safeguard’s businesses were effectively being valued at zero by the market.

Over the years, Safeguard’s strategy evolved, and the company sold off much of its stake in Novell, reinvesting the proceeds into other businesses, including private venture capital investments. This shift made Safeguard a different investment from what it was when Baupost first purchased it. Seth noted that the company used the proceeds from Novell to pay down bank debt, which improved Safeguard’s financial position. Additionally, Safeguard began focusing on a smaller group of promising companies, aiming to concentrate on businesses with greater growth potential.

Hepointed out that Safeguard’s holdings in Novell and CompuCom nearly explained the company’s entire market capitalization. Safeguard owned approximately 70% of CompuCom, a computer reseller, and the combined value of its stakes in Novell and CompuCom was greater than Safeguard’s market capitalization. In addition, Safeguard held stakes in other technology companies, such as Coherent, Tangram, and Sanchez. Klarman described Safeguard as a “closed-end fund trading at a substantial discount” to the value of its underlying holdings.

Despite the challenges Safeguard faced, The Oracle of Boston saw it as a unique opportunity to gain exposure to a portfolio of technology companies at a discounted price. He recognized the inherent risks of investing in technology businesses, given his overall skepticism about the market and economy. However, he viewed Safeguard as a way to own a diversified portfolio of technology investments at a “negative price,” since the value of its stakes in Novell and CompuCom alone exceeded its market cap.

Safeguard was a shareholder-friendly company. Insiders were the largest group of shareholders and that there had been recent insider buying, including purchases by the company’s chairman, Warren Musser. Over the years, Safeguard had taken actions designed to benefit shareholders, such as stock buybacks after the 1987 market crash, spinoffs, and rights offerings that allowed shareholders to invest in underlying companies at attractive prices.

Although Klarman acknowledged that Safeguard had been a somewhat frustrating investment for Baupost, he believed that the company’s accumulated wisdom and experience in venture capital, combined with its significant discount to intrinsic value, made it an attractive opportunity.

Summary

Seth Klarman’s rare 1991 interview provides a masterclass in value investing, capital preservation, and contrarian thinking. He explains Baupost’s disciplined approach, emphasizing holding cash when bargains are scarce, a strategy that helped them navigate the 1987 crash successfully. Klarman critiques institutional investors’ short-termism, warning that indexing could amplify market downturns, and questions the "buy-the-dip" mentality, arguing that past recoveries may not always repeat. His bottom-up strategy focuses on mispriced securities, distressed debt, and asset-rich businesses, avoiding speculative growth stories. Highlighting investments like Columbia Gas System, Esco Electronics, and Safeguard Scientifics, Klarman reinforces his belief in a margin of safety, flexibility, and patience, offering timeless lessons for value investors.

Do you wanna learn how to invest like Seth Klarman?

Buy my new ebook Deep Value Investing: The Essential Guide.

With this ebook you’ll be able to:

Learn how Seth Klarman’s methods still apply today and why they’ve stood the test of time.

How to find and value deep value situations

See how deep value investing works in real scenarios

Got a burning question or a topic you're curious about? I'd love to hear from you! Please drop a comment 💬 below or shoot me an email 📧 at worldlyinvest@gmail.com